Blockchain — the system of decentralizing a database and distributing it across an entire network of computers — brought us Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. It’s been used to make supply chains more transparent and create secure records that cannot be altered unilaterally.

Now the technology is being used in the COVID-19 immunization program of Britain’s state-owned National Health Service.

The vaccines need to be stored at frigid temperatures to be effective. In the case of the Pfizer shot, the required range is minus 60 to minus 80 Celsius.

“Storing the drugs in the correct way is absolutely critical,” said Tom Screen, technical director of the British technology company Everyware.

The company is using sensors and cloud computing to remotely monitor the temperature of NHS refrigeration units.

“If a fridge does go out of the temperature range, the hospital gets an automated alert,” Screen said, adding that without such notification the hospital could be forced to discard precious vaccine supplies.

Data security is a crucial part of Everyware’s modus operandi, especially when it comes to NHS facilities. The health service suffered a serious cyberattack in 2017 and was subsequently criticized in a parliamentary report for being unprepared for hackers.

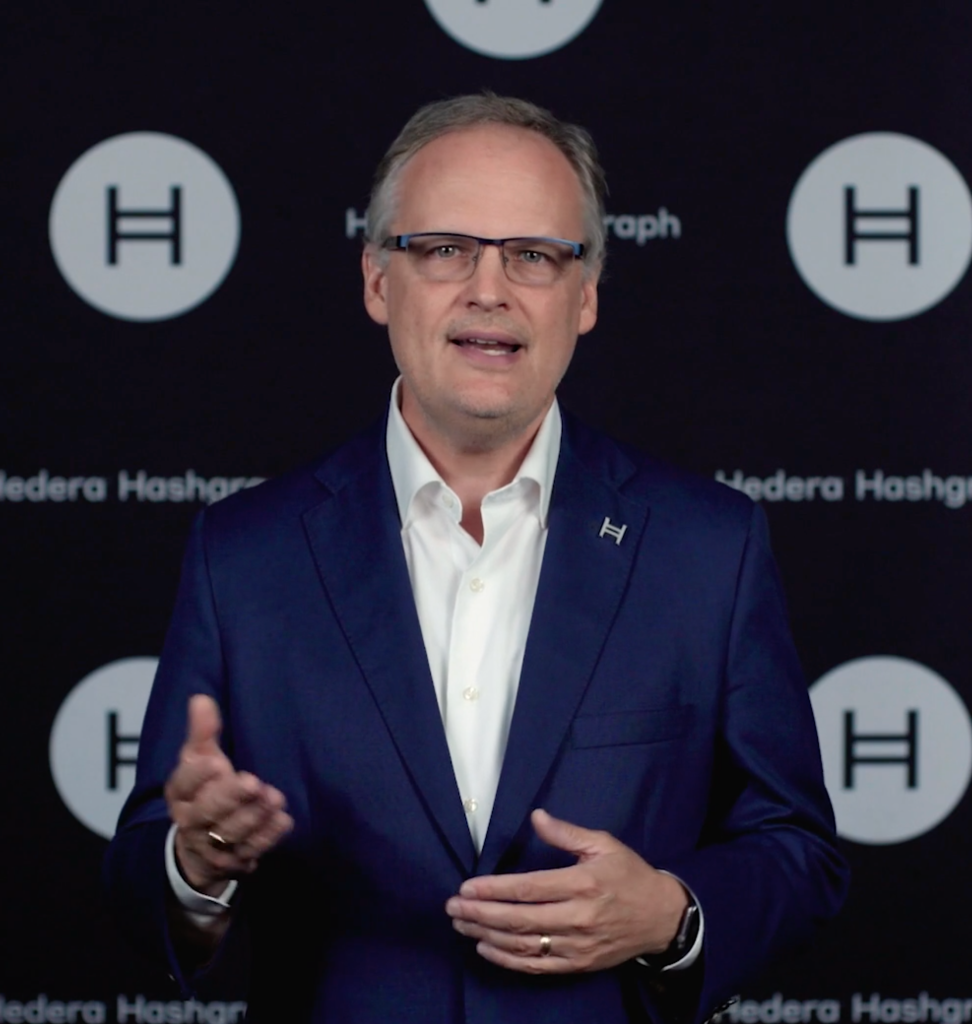

To help with cybersecurity, Everyware has turned to Hedera, a U.S.-based platform that offers a distributed ledger technology like blockchain, which gave birth to Bitcoin. Hedera CEO Mance Harmon said it’s ideal for a COVID-19 immunization program.

“Having a tamper-proof record-keeping system that can be shared across the vaccine supply chain is always important, but critically so here for the COVID vaccines,” Harmon said.

Hedera’s chief executive believes that decentralized computer networks with hundreds or even thousands of participants can play an important role in other aspects of pandemic management — to combat vaccine counterfeiting, for example, and create unforgeable vaccination certificates.

Trust is the key, according to Jillian Godsil, an author who’s written extensively about blockchain. She said that as the pandemic has spread insecurity, distributed ledgers have come into their own.

“People can lie. Institutions can lie. Governments can lie. But blockchain cannot lie,” she said.

As a result, Godsil said, more and more people are entrusting their health — and not just their wealth — to this technology.

What’s the outlook for vaccine supply?

Chief executives of America’s COVID-19 vaccine makers promised in congressional testimony to deliver the doses promised to the U.S. government by summer. The projections of confidence come after months of supply chain challenges and companies falling short of year-end projections for 2020. What changed? In part, drugmakers that normally compete are now actually helping one another. This has helped solve several supply chain issues, but not all of them.

How has the pandemic changed scientific research?

Over the past year, while some scientists turned their attention to COVID-19 and creating vaccines to fight it, most others had to pause their research — and re-imagine how to do it. Social distancing, limited lab capacity — “It’s less fun, I have to say. Like, for me the big part of the science is discussing the science with other people, getting excited about projects,” said Isabella Rauch, an immunologist at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Funding is also a big question for many.

What happened to all of the hazard pay essential workers were getting at the beginning of the pandemic?

Almost a year ago, when the pandemic began, essential workers were hailed as heroes. Back then, many companies gave hazard pay, an extra $2 or so per hour, for coming in to work. That quietly went away for most of them last summer. Without federal action, it’s mostly been up to local governments to create programs and mandates. They’ve helped compensate front-line workers, but they haven’t been perfect. “The solutions are small. They’re piecemeal,” said Molly Kinder at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program. “You’re seeing these innovative pop-ups because we have failed overall to do something systematically.”