“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Alex Bauer, head of product marketing at Branch.

Less than a month ago, on March 15, the Financial Times broke a remarkable story. A state-backed consortium known as the China Advertising Association representing more than 2,000 of the biggest names in Chinese tech, has been quietly testing a new standard called the China Advertising ID (CAID).

Normally, something like this wouldn’t be particularly newsworthy. The Chinese tech world is full of homegrown standards. But CAID represents something much bigger: it’s an overt attempt to bypass Apple’s upcoming AppTrackingTransparency (ATT) policy.

In other words, Chinese apps are basically forming a union and daring Apple to ban all of them at once.

It’s audacious. But how does CAID work, why is it different from typical attribution techniques and what might Apple do about this tricky situation? Let’s dive in.

How CAID works

Shared platform identifiers, such as the IDFA on iOS and the Google Advertising ID on Android, are perfectly suited to measuring digital ads. This is because the same ID is available for all events, so it’s simple to connect ad touches with conversions.

But after Apple’s ATT policy goes into effect, IDFAs will be unavailable in the vast majority of cases, which means these traditional measurement flows will break.

CAID is essentially an open standard intended to function as a drop-in IDFA replacement, and there are two key characteristics that appear tailor made for this purpose:

- CAIDs are designed to be persistent. Unlike many other measurement techniques, the CAID process creates a universally unique identifier (UUID) value that can be stored and reused. There’s even functionality built into the spec to provide mappings between CAIDs when the algorithm receives updates for better accuracy.

- CAIDs can be generated by any participating company. Even though a CAID isn’t attached to the device at a hardware or OS level, following the same process to generate a CAID multiple times on the same device will (in theory) generate the same identifier each time. While this isn’t as accurate as a platform identifier like the IDFA, it is the next best thing and can be used in most of the same ways.

In a nutshell, CAID harvests an array of metadata parameters from the device and combines them in order to generate an identifier that is most likely “unique enough” for the purposes of ad measurement.

How a CAID is made

The technical process to generate a CAID is fairly simple:

1. Collect data parameters from the device. The CAID documentation provides sample code methods for app developers to do this, though it would also be quite simple to integrate the process into various third-party SDKs in future.

2. Send collected parameters to an API endpoint. The data is serialized and encrypted before transmission. Today, the API endpoint is owned and operated by the China Advertising Association, although this could change in future to be multiple API endpoints implementing the same spec or possibly even local generation on the device.

3. API returns a CAID value. This value can then be used in place of an IDFA for purposes such as attribution.

This process takes place wherever a CAID is called for, meaning both advertiser and publisher apps would perform the same steps.

Although I won’t get into it here, it’s important to point out that there are some obvious concerns related to fraud that will need to be addressed if this spec survives through to real world implementation.

Example device parameters used for CAID generation, from the CAID spec document.

The CAID spec fits all the criteria of a “fingerprint ID,” which is hardly a new concept in the digital ecosystem.

IDs of this sort have long been used for web-based tracking, and the reason we haven’t seen widespread adoption in mobile apps is mainly because they’ve been largely unnecessary. Platform identifiers like the IDFA provided the same benefits, but with more reliability.

But here’s the mind-blowing thing: What’s unique about CAID isn’t the technical implementation – it’s that Apple’s AppTrackingTransparency policy appears to have provided the catalyst to get the entire Chinese mobile industry to cooperate on a shared implementation.

How is CAID different from traditional mobile attribution?

Prior to iOS 14, IDFAs were a primary attribution method for mobile measurement providers (MMPs) – although there have always been situations where IDFAs weren’t available, such as when users had Limit Ad Tracking enabled or a web click on an ad led to an app install.

In these situations, MMPs typically fell back on probabilistic matching techniques, which were often colloquially termed “fingerprinting” for convenience.

While this might sound a bit similar to CAID, there’s a key difference: MMPs never used these techniques to generate persistent identifiers. The basic ad attribution process can be done more efficiently, and with less risk to user privacy, via the simple, point-in-time matching of basic event metadata, like IP addresses. There was simply no need for MMPs to create a unique identifier that looked like CAID, and after the attribution decision was complete, all of the event metadata could be safely discarded.

Unfortunately, Apple has made it clear that even these point-in-time techniques, while far less invasive than CAID, are still considered forbidden under the new ATT policy.

What happens next?

At a technical level, it must be admitted that CAID is quite an elegant solution. It’s a great example of a cooperative spec that likely never even would have gotten off the ground without Apple pushing everyone out of the boat first.

For its part, Apple obviously anticipated that fingerprinting-based IDFA workarounds would pop up, and therefore took care to also address these techniques in their ATT policy. CAID perfectly fits Apple’s definition of a “fingerprint ID,” which was explicitly called out as prohibited during WWDC last year.

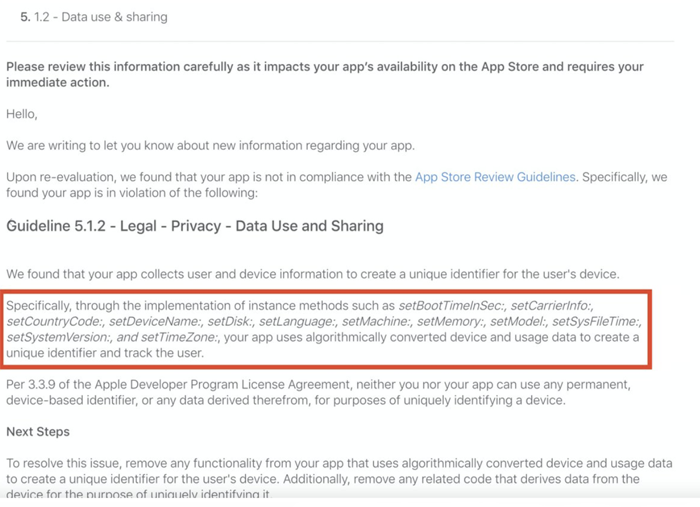

Once the CAID news broke, examples of warnings sent to Chinese developers by Apple quickly started to follow:

Example of warning from App Store review, based on use of CAID.

Re: CAID, I was just shown an app update rejection for a Chinese app for collecting system information used to construct a persistent identifier. I asserted that Apple would not apply a separate standard for ATT compliance for Chinese companies, and it appears that it isnt pic.twitter.com/w0EtQj0vTe

— Eric Seufert (@eric_seufert) March 18, 2021

The code methods Apple references in these warnings directly correlate to the pre-provided data collection functions in the CAID implementation documents, and the language leaves no doubt as to how Apple feels about this kind of workaround.

We likely won’t know the outcome until after iOS 14.5 is released and Apple has built up some ATT enforcement precedent, but here are the two possible extremes:

- Apple successfully cracks down and CAID goes away. This is clearly what Apple is shooting for – but taking on the entire Chinese tech ecosystem, along with its implicit state sponsorship, may end up being a bigger bite than Apple has the stomach for.

- Apple decides to abandon the whole ATT initiative. If CAID manages to get a foothold in China, it would set a precedent for ATT workarounds that could make it impossible for Apple to enforce the policy in a consistent manner globally.

While Apple probably can’t afford to ignore a direct mandate from the Chinese government – if it gets to that point, of course – a public implosion of the ATT initiative would be disastrous for the pro-privacy brand image Apple is trying to build.

The more likely outcome is some sort of behind-the-scenes compromise, where Apple makes a few token enforcement moves and then turns a blind eye … so long as no one pushes the boundaries too far.

This would not be the first example of a selective double standard on App Store policy enforcement, especially for the Chinese market. One obvious template for this would be the way in which WeChat is allowed to run its own “app store” and benefit from far looser standards for in-app payment processing, both of which are technically against the App Store guidelines.

The most unfortunate part is that the real victims in all this are end users.

Although the IDFA-based system definitely had problems, Apple still had leverage and could have chosen to iterate toward a better alternative. Instead, Apple decided to blow up the status quo and start over.

If CAID or something like it is ever implemented, it could be just the first example that Apple’s ATT crackdown may have simply pushed bad behavior underground.

Follow Alex Bauer (@alexdbauer) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.